The message from Beyonce and other outspoken feminists is clear. Women today can be, and do, just about anything. Yet when it comes to social activism, there's one role that women are increasingly falling back on: Mother.

In recent months, a women's gun control group called Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America successfully pressured Chipotle, Starbucks and other major companies into taking a stand against firearms in their restaurants. A group of workers and activists identifying as “Walmart Moms” riled up Walmart by demanding the retail behemoth pay a fair wage. And women affiliated with Corporate Accountability International have used their “MomsNotLovinIt” campaign to pressure McDonald’s to stop marketing to children.

Moms are taking up conservative causes too. One Million Moms slammed Hotwire and Nabisco this year for featuring gay families in ads.

Moms Demand Action protest outside Target's shareholders meeting last week.

Mothers have been cajoling huge companies into changing their ways for more than a century. Though American women now have far greater choices and opportunities, the power of the "mom" has only increased. In part, that's because women are a huge consumer force. Globally, they control about $29 trillion in spending, according to a recent study from the Boston Consulting Group. And companies obsessively focus on pleasing women and mothers. In the U.S., women are responsible for about 73 percent of consumer spending, said Michael Silverstein, the author of the study and a book called Women Want More.

Yet, the idea of "mom" that these companies and groups seem to rally around can seem a little old-fashioned. Companies often direct their marketing to women simply by “hiring a female spokesperson and coloring the product pink,” Silverstein said. A few years ago, Dell saw huge backlash after launching a line of pink laptops aimed at women.

Still, part of the success of this mom-led consumer activism is because companies are so eager to attract a more "traditional" image of moms to their brand.

“The companies that all these moms have been organizing around see moms as a demographic they explicitly target, which is part of the reason moms organizing is both so important and so effective,” said Anna Lappe, a mother of two who has helped organize the MomsNotLovinIt campaign.

"We may still be holding on to expectations of what motherhood means and we may feel like we have to play out a particular role," said Jenny Darroch, a marketing professor at Claremont Graduate University's Peter F. Drucker and Masatoshi Ito Graduate School of Management. "So when women protest in favor of things that favor their children, people may support them because they're acting in a way that people expect them to behave."

Companies’ obsessive focus on satisfying an outdated mom image -- like a 2012 McDonald’s ad featuring a mom watching her kids play at home and then rewarding their good behavior with McDonald’s -- may be costing them though, Darroch said, because many women toggle between roles as workers, moms and partners.

"What's saddening is that (companies) put all women in the same bracket, they stereotype us in the '60s and '70s and they market to us in the role as mother, but they forget that we have other roles that we fulfill," said Darroch, the author of the forthcoming Why Marketing to Women Doesn't Work.

This approach also leaves out dads, who increasingly are taking on more parenting duties, which may include choosing products that are best for their families and kids. The number of dads who are staying at home has skyrocketed in recent years to 2 million in 2012, according to the Pew Research Center. Fathers made up about 16 percent of stay-at-home parents in 2012, according to Pew.

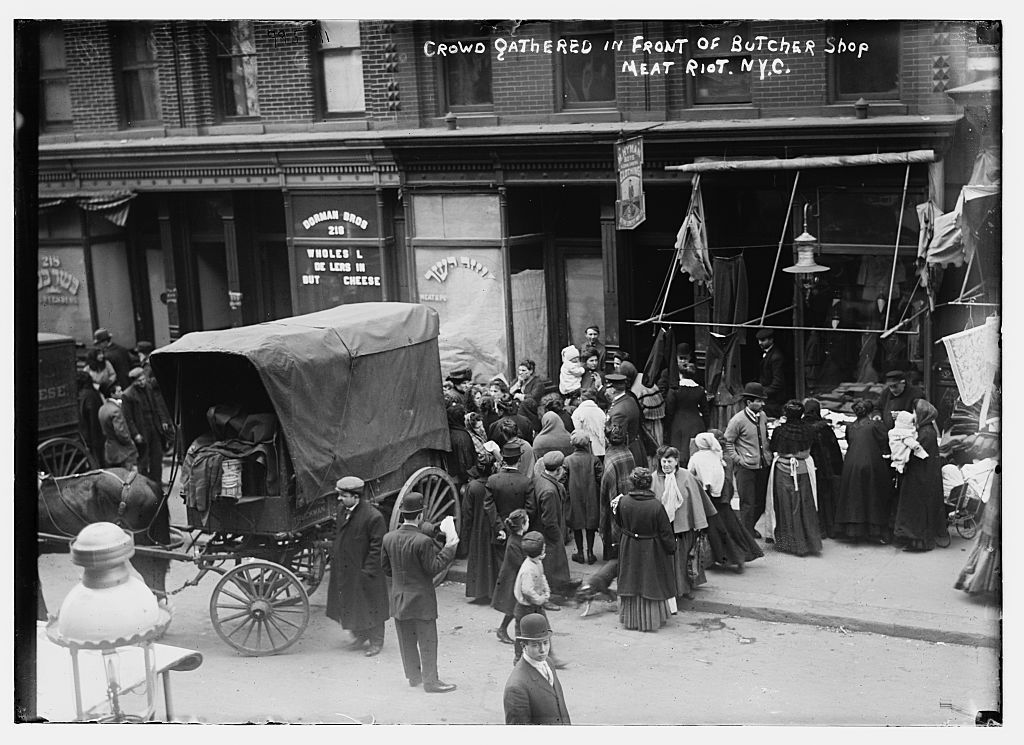

Still, mothers have more experience playing up their demographic power, and have been doing it for centuries. As early as 1880, they organized largely successful boycotts of local businesses that paid workers low wages or wouldn’t allow them to unionize, said Lawrence Glickman, the author of Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in America. In the early 20th century, New York City Jewish women famously used their position as “respected figures in the neighborhood” to organize a boycott of kosher meat sellers that they accused of price gouging, writes Judith Reesa Baskin in Jewish Women in Historical Perspective.

“One of the things that consumer activists have tried to do is take abstract issues and make them very concrete,” said Glickman, the chair of the history department at the University of South Carolina. “I do think the issue of the mom as a political actor is one way that consumer activists have been very successful over time in doing that.”

That tradition of women holding their grocery stores and meat producers accountable for too-high prices continued throughout the 1960s and '70s. While historically many of these groups primarily identified as women and not as moms, that’s likely because at the time, motherhood was assumed to be the primary identity for most women, Glickman said.

“When I look at those movements, I don’t recall a lot of emphasis on motherhood per se, but clearly there’s a lot of emphasis on women as family leaders and as the lever of consumption in the family,” Glickman said.

Protesters riot outside a butcher shop during an early 20th century meat boycott.

Women have also figured largely in consumer movements that affect them less directly, like temperance, Japanese silk boycotts during World War II, and the late-1960s and early-1970s grape boycott aimed at improving conditions for migrant farmers, Glickman said. Mothers Against Drunk Driving claims drunk driving has been cut in half since its founding in 1980 by a California mom whose daughter was killed by an intoxicated driver.

“Over the course of the 19th and 20th century as consumption became seen as the force that drove the economy and therefore a very powerful force with unique kinds of power, this potential power seemed to be accruing to (women), because women were seen as the primary consumers for families,” Glickman said.

That dynamic remains true.

The result is that women are likely paying more attention to what companies are saying and doing and are therefore more likely to engage with them, according to Brayden King, an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

In addition to paying attention, King said moms are great at building consensus and generating publicity, a power that’s been enhanced by social media, given that mothers are some of the most active users of Facebook, according to a November 2013 study from Experian.

Shannon Watts, the founder of Moms Demand Action For Gun Sense in America -- the group that's pushed gun policy changes at Starbucks, Chipotle, Target and others -- started her organization by launching a Facebook page the day after a gunman killed 26 people at Sandy Hook elementary school in December 2012.

“I live in Zionsville, Indiana, and I thought what can I do from here? And what I knew how to do was create a Facebook page,” said Watts, a mother of five. “Because of the strength of social media among women and mothers, I very quickly had thousands of offers of support.”

The Facebook page of Moms Demand Action.

But probably moms’ biggest asset in enacting corporate change is their ability to make a good story, King said. “When moms get behind something and are trying to cast blame on the company, it creates a nice story to tell for journalists and usually there's going to be some moral outrage behind the boycott, which makes for a nice narrative,” said King, whose research focuses on how social movement activism influence corporate responsibility.

That’s important, since the success of a boycott nowadays is very rarely determined by how many people protesters can convince to stop shopping at a store and instead by the level of negative publicity the campaign generates for the company, King said.

“Among those boycotts that get at least some national media attention, 25 percent lead to some sort of public concession on the part of the firm thats being boycotted,” King said. “The key to that is the national media attention. Boycotts that don’t get any kind of national media attention are completely ineffective.”